Analysis of Kompas Newspaper in Indonesia’s New Order Era: Ideology, Hegemony & False Consciousness

- E. Deborah Kalauserang

- Nov 24, 2020

- 5 min read

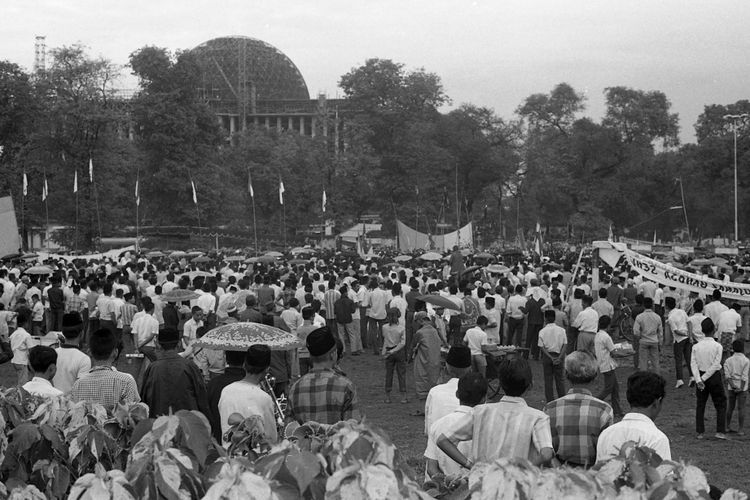

Image source: Kompas.com

According to John Storey in Routledge’s Cultural Theory and Popular Culture (p. 21-22), culture is about signifying practice, “allowing us to speak of soap opera, pop music and comics as an example of culture,” and referring to them as ‘texts’. There are various cultural texts as mentioned before, and among them is the newspaper medium.

Newspaper is made up of its press system, “the overall configuration of the hard-ware, personel and mode of operation of a country’s mass media” (Razak, 1985). A particular press system is a signifier that “reflects a country’s economic, social, political and even geographic conditions” (Razak, 1985), which are the signified entities. In Indonesia, there are various news medias reflecting its economic, social, political and geographic conditions. Among them is the well-known Kompas Newspaper.

As Indonesia entered the New Order era under Soeharto’s regime in 1966, Kompas became a significant medium to voice the people’s aspirations towards the political changes occuring in that time. However, Kompas experienced several changes before and after the New Order era: from being “free, independent and articulate” to a “less idealist newspaper which tends to represent the interests of the rulers, government or even the state which never exercise social control critically, decisively and courageously” (Krissandi, 2018). Why was it so? How did it happen? To find out these answers, theories of ideology, hegemony and false consciousness would be used to investigate this historical phenomena.

The three theories stated above would be reviewed briefly. To begin with, Althusser stated that ideology is encountered in the practice of everyday life and not simply in certain ideas about everyday life (Storey, 2012) As Storey quoted, “what Althusser has in mind is the way in which certain rituals and customs have the effect of binding us to the social order: a social order that is marked by enormous inequalities of wealth, status and power.” Next, Gramsci defined hegemony as a concept of politics that refers to a current condition in a society in which the dominant class rules and leads the society itself (Storey, 2012). Lastly, False consciousness is created to disguise the fact that the dominant class is controlling the masses so the subordinate class doesn’t realize that they are being exploited or oppressed (Storey, 2012).

In the beginning, Kompas was founded by PK. Ojong, Jacob Oetama along with several other journalists, and was first published on June 28, 1965 in Jakarta (Krissandi, 2018). However, according to the Presidential Regulation No. 6 of 1964, the press was required to indulge in one political party (Krissandi, 2018). Moreover, Krissandi in his journal Newspaper “Kompas” in Indonesian Political Constellation stated that “the cold war between the Communist and the Army also encouraged the birth of Kompas.” In addition, he also explained that “it was found that Malari incident (fifteenth of January 1974) was the starting point of Kompas during the New Order era. As a result, Kompas could not be free from the interest of the ruling party.

Tjipta Lesmana in Abar’s Kisah Pers Indonesia (1995) described that Kompas’ role resembling a watchdog changed drastically into some kind of a “spokesman” for the government’s official statements (Abar, 1995). Previously, before the Malari incident, Kompas vocally stated in their article Criticism Not Hurt (published in May 5, 1967) that:

“the function of the press is no different from other democratic institutions that are: to bring the voice of the people, to exercise control, criticism and correction on any form of violence so that power is always beneficial for the implementation of the welfare of the community. We want to affirm again, the purpose of such a function of the press if positive. To keep the power from being abused.”

(Kompas, 5 May, 1967)

As the incident took place, Kompas was threatened to be banned. “The threat of banning is one of Kompas’ starting points in its ideological change,” explained Krissandi, and it “changed drastically (to) become elite-bureaucratic.” The ideological change of Kompas was also shown in their article entitled Integrity of National Leadership, defending Soeharto and his regime as he “blurted out his allegations, rumors and press coverage concerning the President’s family” (Kompas, 22 January, 1974):

“We who listen directly to the President’s statements, draw conclusions, the information is honest, what it is. In place, we all believe in the integrity of national leadership.

The Integrity of National Leadership is important, new there is no doubt, even the traces, but surely, the President will continue to clear up the presidential environment and eradicate the misconduct that the society hopes.”

(Kompas, 22 January 1974)

It was an ironic reality that Kompas’ original voice of criticism and aspiration was silenced by the power of the oppressing regime. Its colors of true idealism was forcefully overlaid by the hegemony of the New Order, writing about the false consciousness happening in Soeharto and his government. As Razak described in his sub-chapter The General Characteristics of The Indonesian Press, Kompas was considered favorable to the government regime (in the era of Soeharto), with the distribution of assertiveness of newspaper measured by 53.1%. Unfavorable = 29.8%, neutral 17.1%. Instead of being confrontative, Kompas editorials chose to ‘refine’ their critics on certain matters (Razak, 1985). Here is the excerpt of the issue on 5 March, 1983, questioning Soeharto’s use of power, his account to the Assembly:

“The presidential address specifies authority as a means of serving the people’s interests. In practice, public service is rendered by the government agencies, officials and civil servants.

An authority does not warrant arrogance on the part of its holders. Instead, an authority dictates modesty and devotion to the people.

No power is free from accountability and public scrutiny. In assessing the bureaucratic service, we should be honest to admit that people in general still have legitimate reasons to complain over public service rendered in return for (illegal) favors.”

(Kompas, 5 March 1983)

Kompas Kompas’ drastic transformation from a ‘watchdog’ to a ‘spokesman’ of the New Order era is an ideological encounter is marked by the inequality of wealth, status and power, as Althusser argued previously. Moreover, hegemony is also seen in this phenomena as the dominant party, the government, pressured threat towards the weaker and retaliating party, Kompas Newspaper. Lastly, the false consciousness created in post-Malari Kompas’ articles disguised the fact that there was control and exploitation of the dominant class over the oppressed, subordinate class.

From the explanations above, it could be concluded that the post-Malari Kompas was utilized as an ideological tool, a product of the political hegemony and a medium to deliver the images of false consciousness in the New Order era. Hence, Kompas functioned as the signifier of the situation of the New Order era, and furthermore, cultural text in the realm of Indonesia’s political unrest of the time.

***

References

Storey, John (2002). Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Razak, Abdul (1985). Press Laws And Systems in ASEAN States. Jakarta: The Permanent Secretariat of The Confederation of ASEAN Journalists.

Krissandi, Apri Damai Sagita (2018). International Journal of Humanity Studies Sanata Dharma University, 1(2), 214-227.

Comments